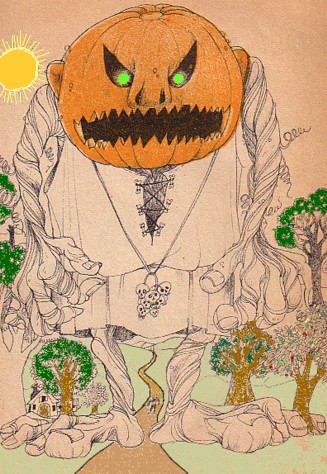

The image in the banner above (and if you’re reading this after the first week in November, you can still see it here) comes from a story called “The Pumpkin Giant,” which I remember reading when I was small. I went looking for the text, and was delighted to find it online.

Now, I am almost certain (though not quite, because I can’t find confirmation of this online) that I first encountered this story in a volume of the New Junior Classics, which we owned in the well-worn, no-frills edition—ten volumes, put out by P.F. Collier; I’m pretty sure my family got its set as a premium with the purchase of Collier’s encyclopedia, which would’ve been 1951 or so. The picture in this Craig’s List Vancouver listing sends me into little spasms of nostalgia and longing, and I know I’m not the only one to remember their quirky charms.

These books provided my first exposure to all the things that make me what I am; it’s not overstating my case to say that. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (with those menacing Tenniel woodcuts), Carl Sandburg’s Rootabaga stories, Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Norse mythology, the Mabinogion, Irish legend by way of Padraic Colum, Edward Lear, Thackeray’s fairy tales, folktales from Russia and India, the Grimms, sentimental but perfectly-formed Victorian fictions like Susanna’s Auction and When Molly Was Six and Nelly’s Hospital, reams of good poetry, stories from the Arabian Nights, the Shakespeare tales of Charles Lamb—the breadth and depth of material in this short shelf of books was staggering. There was always something I wanted to read here.

I was able to find “The Pumpkin Giant” online, of course, because it has fallen into the public domain. (Indeed, whole volumes of The Junior Classics are now PD, and can be found in plain text form at Project Gutenberg.) But I have a sneaking suspicion that the story was in the PD long before I first found it—perhaps even before the original 1938 edition of The Junior Classics. I suspect that was both the method and the point—Collier’s could afford to give away five thousand pages (!) of quality material because they spent nothing (or next to) on rights acquisitions, and otherwise-out-of-print children’s literature was rescued from total obscurity.

This was possible in 1938. It could never happen now, so thoroughly have the copyright laws of this nation been rewritten—largely under pressure by, and for the benefit of, a single gargantuan transnational media conglomerate, and to one purpose: to keep a single cartoon,“Steamboat Willie,” and by extension That Fucking Rodent, from falling into the grubby hands of people who might actually do something of interest. Disney’s tide lifts all boats, in theory, and now all creators (and their executors) are afforded extended protections under the law.

This puts me in a bind, ethically. As a creative person and an advocate of free expression, I believe in the Creator’s Bill Of Rights; I believe that creative people should be able to reasonably expect to not get ripped off. But there’s a part of me that understands that stories want to be read; that information wants to be free; and that the public domain, the commons of ideaspace—quality work, freely available—is an absolute good; it feeds readers, and it rescues out-of-print works. The listings on ManyBooks keep track of downloads, and I’ll tell you, it’s the Long Tail theory in action. There’s an audience for everything (or nearly); and if not for public domain, they’d never get this thing they wanted—probably never even know they wanted it. And that would be sad.

Beating back ridiculous copyright laws—copyfight—is a hard sell, because the idea of somebody owning his or her creative work is a no-brainer; it plays on our inherent sense of fairness. And it’s not a sexy issue; when the BoingBoing folks go on about it, I’ve got to admit, my eyes glaze over.

But I need to be honest, and think about how much of the work that influenced me most—the fiction and poetry I read as a child—was available to me in cheap, mass-market edition because of copyright laws as they existed at the time, and how the work that should influence the next generation of creative persons will be kept from them by the eye on the bottom line.

You can’t debate it in terms of profit and loss; but I believe that without public ownership and easy availability of these imaginative works, we are all the poorer.

No comments:

Post a Comment